Hey there every peoples.

Guess what… It’s my 100th post!

When I started this thing 5 years ago, i didn’t know it would grow into the marginal success it is today. But what do you do for such a special occasion? Can’t just be some run of the mill topic. It can’t be the epic rant/expose on that terrible situation almost a year ago (i wouldn’t want to soil the mood with that sordid affair). Luckily, a recent article by good ol’ Brian Switek gave me an idea.

The giant tantrum thrown by the dinosaur fanboys over the upcoming film Jurassic World also played a role. I’d say it’s all been rather pathetic (one guy on Facebook seems to have what can only be called a personal vendetta against the movie) and short sighted. Dinosaurs overwhelmingly dominate all things prehistoric. Movies, books, tv, documentaries, and museum displays. People see giant skeletons they automatically assume it’s a dinosaur. Whenever I tell people I’m pursuing paleontology, they automatically assume it’s about dinosaurs. But it still doesn’t seem to be enough for the fanboys. They are getting another love letter to their beloved “terrible lizards” but it’s still not enough. I’ll save that for another post to avoid a ranting tangent. Point is, dinosaurs reign supreme in the public conscience.

But prehistory doesn’t begin and end with them. The period after the dinosaurs, the Cenozoic era, hosted (and continues to host) a staggering diversity of creatures equally as awesome. In fact, I’d go so far to say that many of the denizens of the Cenozoic are even more spectacular than dinosaurs. That’s just me, but hopefully you’ll understand why at the end of this post. Switek’s article was brief and only touched upon mammals. While mammals dominate the Cenozoic, they weren’t the only ones to experiment wildly with size, shape, and extreme adaptations. There are so many you could write a book about them. Hell, this post was originally supposed to contain 30 entries. But I had to cram in 5 more, and even then it was only achieved by making some of the entrants share slots. So without further ado, here is my list of 35 Cenozoic Creatures as Awesome as (or even more so than) as Dinosaurs.

- Deinotherium

Proboscideans are among my favorite prehistoric animals. So let’s start off with one. Deinotherium was an oddball even compared to the elephants we’ll see later. T has a longer neck then you would expect. And it’s bloody big too. The largest species is a contender for one of the largest mammals ever. What? Oh right. Deinotherium is best known for its tusks. Many (if not most) ancient elephant lineages had lower tusks in addition to upper ones. But not only does Deinotherium lack upper tusks, but its lower tusks have grown down and back like a giant pair of fangs. This has lead to their unofficial nickname “hoe-tuskers”. But just how they were used is still a mystery. Did they use them to dig up roots and tubers? Were they used to pull and rip branches? Or were they used to strip bark from trees, the oldest of the hypotheses? Who knows if we’ll ever know, since there is nothing else like Deinotherium today or in the fossil record. So naturally that made it a great opener for a post like this.

![A pair of Deinotherium wander through the forest of Miocene Europe. By Mauricio Anton, from "National Geographic's Prehistoric Mammals"]()

A pair of Deinotherium wander through the forest of Miocene Europe. By my all time favorite paleo artist Mauricio Anton, from “National Geographic’s Prehistoric Mammals”

![]()

skeleton of Deinotherium at the Stuttgart Museum, Germany. From Wikipedia

![]()

Skull of Deinotherium giganteum at the Oxford Museum of Natural History. From Wikipedia

- Amphicyon

Dogs are cool. So are bears. So you’d think a mashup of the too would be super cool. Well that is kind of what we have in Amhpicyon. It is the largest (and arguably the most successful, judging from its presence on 3 continents and nearly 8 million year existence) of the bear-dogs. They got that name because early scientists thought they were ancestral to both dogs and bears since they had traits of both. But we now know that dear-dogs were their own distinct group, the Amphicyonids. They have no modern descendants or close relatives. Apmphicyon was essentially the biggest carnivore of its time and place. It undoubtedly ate whatever it wanted. This obviously differed over its range. For example, study of a bonebed in Spain suggests one species regularly preyed on smaller fare like deer. The largest species, Amphicyon major, it’s estimated to have weigh over 600 pounds. All species, however big, possessed large skulls with powerful jaws and sharp canines. I think I’d want this guy on my side in a prehistoric bar fight!

![Cast skeleton of Amphicyon at the Raymond Alf Museum of Paleontology.]()

Cast skeleton of Amphicyon at the Raymond Alf Museum of Paleontology.

![]()

A pair of Amphicyon major fight over a hot lunch in the middle Miocene wilds of Spain. By Mauricio Anton

- Titanoboa

Funny story. When i was a kid we would go to brunch on mother’s day and then a movie afterwards. I am not exactly sure how, but we ended up going to see Anaconda. Because nothing says “celebrating motherhood” like watching people get eaten by a giant snake! The movie of course had to take liberties with the anaconda’s size so it could prey on humans. Anacondas are the heaviest snakes on earth; pythons are longer, but not as massive as anacondas. Estimating the size of anacondas is very difficult and so we don’t truly know how big they really get. Specimens over 20 feet long and weighing over 200 pounds have been reported. Now these snakes have been reported to attack humans (with a couple bodies being found bearings marks of the anaconda’s MO). While certainly capable of killing a human, they are unable to eat them. While anacondas can eat prey the size of a small deer, a capybara, or the smaller caimen species, these prey items are all somewhat narrow. Even the extraordinary flexing and stretching of a large snake skull can’t hope to get around a human’s broad shoulders (I had heard it hypothesized that a monster snake could swallow a human if they repositioned so that the shoulders are vertical, not horizontal. But even that seems like a stretch. No pun intended).

I tell you all this because even bigger snakes have been found in the fossil record. Wonambi of the Australian Pleistocene is the usual reference, but at 15-18 feet it is no bigger than a modern rock python. Go back further to the Pliocene and we find Australia’s true monster snake. Known as the Bluff Downs giant python, this snake is estimated to have measured 30 feet long and had the girth of a dinner plate. But fossils from the Eocene of Egypt hinted at an even bigger serpent. This snake is estimated to have stretched to 36 feet long. For a while this snake (Gigantophis) was the record holder. That is, until 2004 when paleontologists began trolling the Paleocene rocks of a Columbian coal mine.

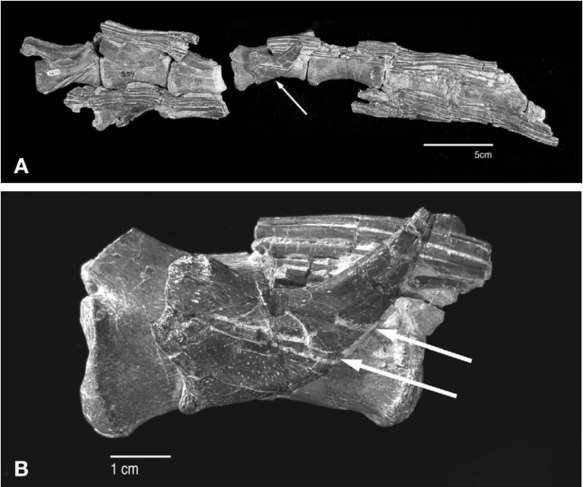

The scientists found huge turtles, a wide array of crocodiles, fish, leaves, fruits, and seeds galore- the remains of an entire ecosystem, rivers and rainforests teeming with life. But something was off. The kept turning up strange vertebra. They looked like snake vertebrae, but at over 5 inches across they were far bigger than any other snake vertebra known.

![]()

On the left is the vertebra of Titanoboa. On the left is a vertebra from a 17 foot anaconda. From the website of the Florida Museum of Natural History

The snake was christened Titanoboa, the largest snake that ever lived. Based on the fossils found, it is estimated that Titanoboa was 42 feet long and weigh as much as 1.2 tons. It would have been an unthinkable 3 feet across at its widest point. Truly a monstrous reptile. Study of the plants found alongside it revealed why Titanoboa and its fellow reptiles at Cerrejon got so big. During the Paleocene global temperature was much higher than it is today. To give you an idea of how high, check out this lush forest:

![OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA]()

A hippo-like pantodont feeds in an Eocene swamp. Taken from the exhibit “Extreme Mammals”

That is Elesmere Island. Of the coast of Greenland. Well above the arctic circle! The tropics (where Columbia resides) are notorious for being hot and humid today. Well it was even more so ~60 million years ago. Reptiles are ectotherms, meaning their body temperature is dictated by their surroundings. Large reptiles need a constantly warm environment or they will freeze to death. Since it was insanely warm during the Paleocene, this allowed reptiles to go supersize. One turtle from Cerrejon had a shell 6 feet long and over 3 feet wide- about the size of a pool table!

![]()

Shell of the giant snapping turtle Carbonemys coffrinii. From the website of the Florida Museum of Natural History

Titanoboa was undoubtedly a top predator. What did it eat? There were 6 foot lung fish for starters. There were many crocodiles, ranging from 6 to 22 feet. Most turtles may have been too wide even for Titanoboa to swallow (although smaller juveniles would certainly be fair game). Like it’s modern cousin the anaconda, Titanoboa probably spent most of its time in the water. It’s bulk made it slow and awkward on land; but the water, able to support it’s great weight, allowed Titanoboa to move quicker and more fluid. In a world overrun with giant reptiles, Titanoboa stood out as a terrifying, colossal monster. Clearly it reigned over the ancient Cerrejon ecosystem, unchallenged at the top of the food chain.

![]()

Fleshed out model of Titanoboa devouring a crocodile (with puny humans for scale). By Getty Images, from Wired.com

Or maybe not. Tantalizing evidence hints at another gigantic cold blooded terror prowling the ancient rivers. Remember that six foot turtle shell? You’d think something like that would be relatively invulnerable to predators. But lo and behold:

![Bite marks on the shell of a giant turtle. From "Titanoboa: Monster Snake" by the Smithsonian Channel]()

Bite marks on the shell of a giant turtle. From “Titanoboa: Monster Snake” by the Smithsonian Channel

Even the largest croc known from the site couldn’t have made bite marks like that. What could have? A partial vertebra sheds some light:

![Partial vertebrae of a giant crocodile. From "Titanoboa: Monster Snake" by the Smithsonian Channel]()

Partial vertebrae of a giant crocodile. From “Titanoboa: Monster Snake” by the Smithsonian Channel

![Partial vertebrae of a giant crocodile compared to the vertebra of a saltwater crocodile, the largest extant crocodilian. From "Titanoboa: Monster Snake" by the Smithsonian Channel]()

Partial vertebrae of a giant crocodile compared to the vertebra of a saltwater crocodile, the largest extant crocodilian. From “Titanoboa: Monster Snake” by the Smithsonian Channel

Based on comparison with other crocs, it is estimated the Cerrejon specimen came from an animal 40 feet long. That’s almost as long as Titanoboa (and undoubtedly much heavier)! As if a giant snake isn’t bad enough, we have a giant crocodile as well. And not only that, but multiple giant crocodilians!

- Purussaurus

There must have been something in the water of prehistoric South America. Not only did it produce the largest snake ever to live, but also the largest freshwater turtle to ever live (Stupendemys, with a shell 8 feet long). And it has also produced two contenders for largest crocodilians of all time. We already met one (the Cerrejon mystery giant). But much later in prehistory did another juggernaut would vie for the title. It is called Purussaurus.

![]()

“Om nom nom!” from Dinopedia

Purussaurus has been found in Peru, Venezuela, and possibly Brazil. It is thought to be related to alligators and caimans, based upon it’s short rounded snout and other features. Measurements of fossils peg Purussaurus at over 40 feet long. Biomechanical studies indicate it do the “death roll”. This is a technique used by modern crocodilians to subdue and dismember their prey. And when your head is this big:

![Cast skull of Purussaurus at the Raymond Alf Museum of Paleontology.]()

Cast skull of Purussaurus at the Raymond Alf Museum of Paleontology.

There was virtually nothing this guy couldn’t consider food. The Amazon and it’s tributaries are already considered incredibly dangerous because of all the critters that could kill you. If Purussaurus were still alive today, it would render any river goer petrified with fear.

![]()

Life-size model of Purussaurus at a museum in Peru. By deviant art user Pyroraptor42

- Thylacosmilus

Yet another overlooked but marvelous South American native is Thylacosmilus, the “marsupial” sabertooth. Dinosaurs are always trumpeted as marvels of evolution. But I think the Cenozoic era provides the strongest examples of various evolutionary phenomena. For example, convergent evolution. Convergent evolution posits that animals lving in different parts of the world will evolve similar traits to fill similar niches. And you couldn’t ask for a better example than Thylacosmilus. It looks so much like a sabertooth cat. If you showed it to any lay person (and probably many scientists), they would think it was a sabertooth cat. But it wasn’t.

For most of the Cenozoic era, South America was an island continent, cut off from the rest of the world. The animals there evolved in complete isolation, This allowed many primitive orders of animals to fill the ecological roles occupied elsewhere by more familiar species. Dogs, cats, bears, nimravids, and other carnivores were absent in South Ameica. So several groups of primitive mammals called metatherians rose to the challenge. Thylacosmilus belongs to a group called thylacosmilids. These animals filled the niche occupied elswhere by sabertooth nimravids and true cats.

![]()

Skull of the sabertooth ripoff Thylacosmilus. From Wikimedia.

Originally, these primitive carnivores were thought to be marsupials. But more recently they have been given their own families inside the larger group Metatheria. This has really been itching my brain. Marsupials are famous for reproducing via a pouch. Did metatherians (which marsupials belong to) also reproduce this way? Because Thylacosmilus means “pouched knife”. It would be a little awkward to keep a name like that and not actually be applicable.

![Fleshed out reconstruction of Thylacosmilus. By Mauricio Anton, from "The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives"]()

Fleshed out reconstruction of Thylacosmilus. By Mauricio Anton, from “The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives”

Thylacosmilus was the last and largest of the Thylacosmilids. It died out ~4 million years ago. It is thought that competition from more advanced placental carnivores drove these archaic predators to extinction. But before then, Thylacosmilus undoubtedly reigned supreme. It was short and stocky, like many sabertooth predators. But it walked on the flats of its feet, unlike true cats that walk on their toes. This means thylacosmilus was an ambush predator, using surprie and power in place of speed. Just like most sabertooths are thought to do. Thylacosmilus may have been a fake sabertooth, be he was a damn good fake.

- Megalania*

Another record breaking reptile. While debate goes on over just how big it was, fossils show that it was much bigger than the largest giving lizard, the komodo dragon. Estimates by Ralph Molnar place Megalania at ~18 feet long an ranging from 600-1000 pounds. Of course these are just estimates. The number of Megalania fossils known number in the double digits. The paucity of fossils have made study of its life and evolution quite difficult. But if it was anything like the komodo dragon, than Megalania was certainly a top predator. There was probably nothing it couldn’t tackle, although the 3 ton Diprotodon may have been too much even for it. It has been suggested by some that Megalania may have been venomous like komodo dragons. However, there is no way at present to determine this.

![]()

Reconstructed skeleton of Megalania assembled by Gondwana Studios.

Megalania appears to have died out with the rest of the Australian megafauna between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago. This is suggested to have overlapped with the first humans to have entered the continent. Titanoboa, Purusaurus, and the dinosaurs all died out long before hominins walked the earth. But Megalania was around when humans were. It must have been a terrifying sight to the first Aborigines. Humanity at that point likely had experience with lizards a few feet long tops. But now they were confronted with a beast the size of a grizzly bear. Given these early people were armed only with spears and javelins (both probably consisting of sharpened sticks with fire hardened tips), Megalania must have been a worthy adversary.

![]()

A scene set in the Pleistocene of Australia. One Megalania feeds on the carcass of the rhino-size marsupial Diprotodon. Another Megalania, perhaps attracted by the smell of the kill (or carrion) approaches from the left. By one of my favorite paleoartists Mark Hallet. Used as the cover for “Dragons in the Dust: the Paleobiology of the Extinct Lizard Megalania” by Ralph Molnar.

In my post about Megalania, I alluded to a study by an anthropologist who thinks Megalania may have survived into the Holocene. They base this idea on analysis of a legend told by a tribe of southwest Australia. This sort of thing is exceptionally hard to prove, especially since science pays no heed to anecdotal evidence. But it may be equally hard to disprove, since Australia’s poor fossil record (compared to other continents at least) has provided so few fossils of Megalania and dingoes. It seems this awesome predator has many secrets yet to be revealed.

*(yes, I’m using the old name Megalania, even though it was officially changed to Varanis priscus. Ralph Molnar in his book said Megalania would probably live on as the common name. So that is what I’m doing. Because a name that translates to “giant ripper” is too awesome to let fall by the wayside. Besides, if Brian Switek can attempt to make the nickname “shovel-beaked” a thing, then I reserve the right to try to make Megalania the all too apt nickname of this “true dragon of the past”.)

- Procoptodon

Kangaroos are the pretty much the official symbol of Australia. They are a ubiquitous feature of the landscape And at 150 pounds, the red kangaroo is the largest living marsupial. But not so long ago there was a kangaroo that put the modern champ to shame. Called Procoptodon goliah, it was the biggest kangaroo known. Standing 7-7 1/2 feet tall and weighing 400 pounds, it was a giant among marsupials. But size alone doesn’t set Procoptodon apart from the rest. It was part of an extinct subfamily of kangaroos called sthenurines. A trademark of these kangaroos was a short face. Procoptodon’s skull looks like a red kangaroo smashed into a wall cartoon style. The short deep skull facilitated powerful chewing muscles, a trait needed to process Australia’s rough forage.

![Skull of Procoptodon goliah]()

Skull of Procoptodon goliah

Sthenurines were also very robust. Their bones are much thicker and heavier in appearance when compared to their more gracile cousins. These animals also possessed a single toe on each foot; in the case of Procoptodon, a large thick claw. It is debatable whether they were as fast as modern kangaroos. Though being browswers, they probably lived in more wooded habitats where speed isn’t as important. Speaking of browsing, sthenurines were capable of reaching up over their heads. They probably used their large claws to hook down branches to get at the leaves. Procoptodon was capable of reaching 9 feet up to grab lunch. It is because of this supposed feeding habit that I think the sthenurines were the Australian equivalent of ground sloths. Sloths are the closest fit, but basically they were the high reaching browsers; the same niche filled elsewhere by camels, giraffes, and deer. A critter further down the list has been suggested as being a ground sloth analogue, but I think these extinct kangaroos are a better fit.

![Life rconstruction of Procoptodon goliah. From National Geographic]()

Life rconstruction of Procoptodon goliah. From National Geographic

Like the rest of the Australian megafauna, Procoptodon is thought to have died out 40,000-50,000 years ago. Whether it was overhunted by humans or wiped out but by climate change is yet to be determined. What a loss I say. Australia’s deep past has always fascinated me. It reached its climax in the Pleistocene, with a fauna unlike anything in the world, before or since. I hope I have you hooked because you’ll be seeing plenty more of them.

- Kelenken

I can hear the dino fan boys now.”You said you weren’t doing dinosaurs. Birds are dinosaurs! Haha, you can’t escape their awesomeness!!!1!”. Look, I won’t dispute the fact that birds are descended from dinosaurs. But I will never see birds proper as dinosaurs. I understand the joy and satisfaction you get in knowing that all those feathered things flitting around the park or your backyard are a physical connection to your favorite prehistoric animals. But does everything have to be about dinosaurs? Can’t a bird be a bird? To me, there is still a gulf of difference between this:

![]()

Great blue heron. Image from Wikipedia

And this:

![]()

Oviraptorosaur from the late cretaceous of North America. Art by Dr. Julius Csotonyi

Birds are a highly diverse, highly successful class of vertebrates. Apparently that means nothing unless we are constantly reminded that they are dinosaurs. Because dinosaurs are the COOLEST THINGS EVER!!! So yes it is technically a dinosaur, but kindly shut the fuck up about it while I talk about a bird that would make Alfred Hitchcock shit his pants.

As I said above South America was cut off from the rest of the world. While many distinct groups evolved to fill the niches fill elsewhere by more advance mammals, perhaps the most curious case is the large carnivore guild. We saw one side of this coin with the metatherian mammals. But the other side of that coin is what usually gets the attention. While the carnivore guilds of the world were dominated by mammals, South America’s landscapes were terrorized by birds.

![]()

Phorusrhacids of different sizes and bilds. By Alvarenga and Hoefling

The group is called the phorusrachids, commonly referred as “terror birds”. These flightless birds appeared in the Eocene epoch and survived until the late Pleistocene. They ranged in size from a stork to Brontornis (“thunder bird”), who towered 9 feet tall and weighed 700 pounds. I chose to do this guy because he’s relatively new and is one of the larger examples. The name Kelenken comes from a god of the local Native Americans where the remains were found (in Argentina, which I am now convinced has the best studied record on the continent). An apt name for a bird with a skull 28 inches long (the size of a horse’s). Also found was a partial foot bone. This foot bone allowed scientists to estimate its size. At 7 feet tall and 400 pounds, Kelenken is one of the larger members of the phorusrachidae.

![Well the photo speaks for itself.]()

Well the photo speaks for itself.

Kelenken was clearly a top predator, but how it dispatched prey is still a mystery. A relative, Andalgalornis, was estimated to run over 40 miles an hour. This hypothesis was reached by studying its surprisingly muscular legs. This would make it the fastest known biped. But the authors favored an alternative hypothesis: that Andalgalornis used its strong legs not to run fast, but to utilize a powerful stomp. This may have been to break open bones to access the nutritious marrow; or it may have been used to kill prey like a modern secretary bird. Keleken may have used a similar kick to kill prey. Or it may have used its strong sharp beak to jab at hapless victims. A National Geographic (before it became the crime channel) documentary suggested it may have been able to prey on the smaller species of glyptodonts by flipping them over and tearing at their vulnerable underbelly. Without more fossils of the predator and prey it’s impossible to say for certain.

![]()

A phorusrhacid tells a group of borhyaenids that this kill is taken.

Terror birds were thought to go extinct at the beginning of the Pleistocene. The cause, according to the hypothesis, was competition from mammalian carnivores. But it doesn’t look that simple. For starters, one species of terror bird called Titanis actually came north into the southeast United States and stuck around for 3.1 million years, amidst all the supposedly superior predacious mammals. Also, a fragment of foot bone of a phorusrachid found in Uruguay dates to just 40,000 years ago. Again, amongst all the “superior” mammalian predators. Was it differences in habitat, diet, or something else? There is a lot more that needs to be done on the terrifying terror birds and the strange world they lived in.

![]()

The end of the terror birds? By deviant artist Egan7

- Odobenocetops

Convergent evolution can cause strange things to occur. So far we have seen a sabertooth cat that wasn’t, birds and lizards as top predators, and giant kangaroos. Now we come to yet another oddball born of the need to fill a niche in his own neck of the woods. During the Pliocene the marine mammal world saw the emergence of the earliest true walruses. What is not to love about walruses? They have a funny name, they make funny sounds, and they just look funny. Their most conspicuous feature is their two long tusks. Males are the ones with the long tusks, which they use to fight rivals; both sexes use their tusks to defend themselves from predators and to hook themselves up onto ice flows. Walruses are perhaps the strangest beasts of the arctic. So tell me: what happens when a dolphin tries to be a walrus?

You get Odobenocetops. This weirdo lived along the coast of Peru ~4 million years ago. The name is translated as “whale that walks on its teeth”. The walrus’s name is Odobenis, which means “tooth walker”. I doubt the name similarity is a coincidence. Anyway this guy is so weird he is placed in his own family, the Odobenocetopsidae. As if a tusked dolphin wasn’t odd enough, Odobenocetops took the weird factor to another level. Females sported tusks one foot long. The males, however, rocked one tusk a foot long and the other tusk three feet long. It is though males used their tusks to spar with each other, much like walruses do. I’m sensing a theme here…

![Cast skull of Odobenocetops at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County]()

Cast skull of Odobenocetops at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

Odobenocetops lived in the warm shallow waters of a coastal ecosystem. It is thought to have vacuumed up mollusks from the sea floor. It would then use its tongue like a piston to suck the tasty invertebrates out of their shells. This feeding style is based on the fact that Odobenocetops possesses a strongly arched palette combined with a total lack of teeth (save for the tusks). How do those features suggest suction feeding? I’ll give you one guess. That’s right. It’s the same equipment used by walruses to suction feed on clams and other shellfish. Odobenocetops was a dolphin everywhere on its body… except its head, where it was a walrus.

![]()

Two male and one female Odobenocetops. From Wikipedia

Not to steal the “walrus dolphin’s” thunder, but he shared his habitat with another complete weirdo. It was called Thallasocnus. It was a ground sloth, an animal usually thought of as slowly pondering around on land. But Thallasocnus was an aquatic ground sloth. Its remains have been found exclusively in marine deposits, the same deposits as Odobenocetops, sharks, and other whales. Modern tree sloths are actually pretty good swimmers, which I guess must be a prerequisite when you live in a forest that annually floods. Scary looking marine reptiles of the Mesozoic capture the imagination of most people. But I would give anything to have seen The Aqua Sloth swimming in the sea.

- The Tuskers

Prehistoric elephants are among my absolute favorite denizens of the fossil record. They have a fascinating, storied history, spanning 45 million years. They journeyed far and wide, becoming prominent members of any ecosystem the settled in. Majestic and grand, their remains dominate most Cenozoic halls. Mammoths and mastodons are the most commonly seen in museums. But during the Miocene there was a diverse group called Gomphotheres. Within this group there was a family affectionately dubbed “shovel-tuskers”.

Fossils of the shovel-tuskers started popping up in the late 19th/early 20th centuries as the American west was tossed and tumbled by paleontologists. But shovel-tuskers didn’t really enter the limelight until the 1920s. Among the many great finds of Roy Chapman Andrews’ Mongolian expeditions was a shovel-tusker bonebed. The remains belonged to Platybelodon:

![]()

Skull and lower jaw of Platybelodon. Image from Wikipedia.

![]()

A small herd of Platybelodon enjoying themselves along the banks of a Miocene river. By deviantart user MrsCoelodonta

![]()

Skulls and jaws of male (top) and female (bottom) Platybelodon from China. Note the broad nature of the tusks and jawbone symphisys. From Wang Shiqi et al, 2013

Andrews described the jaw of this animal as “resembling a great coal shovel… The jaw was five feet long. A truly stupendous organ”. And the analogy stuck.The scientific minds of the expedition, Henry Fairfield Osborn and Walter Granger even went so far as to include this image in their description of the fossils:

![The lower jaw of Platybelodon compared to a shovel. From Osborn and Granger, 1932]()

The lower jaw of Platybelodon compared to a shovel. From Osborn and Granger, 1932

Shovel-tuskers were viewed as using their jaws as scoops. What did they scoop? Well that’s harder to pin down. You see, there wasn’t a standard design. There were many variations:

![]()

Complete lower jaw of Amebelodon (from Florida, i believe). Image from Wikipedia.

![Lower jaw of Amebelodon at the University of Nebraska State Museum. From "The Cellars of Time: Paleontology and Archaeology of Nebraska"]()

Lower jaw of Amebelodon at the University of Nebraska State Museum. From “The Cellars of Time: Paleontology and Archaeology in Nebraska” by Voorhees et al

![Lower jaw of Torynobelodon from Nebraska.]()

Lower jaw of Torynobelodon from Nebraska. From Barbour, 1931

![Lower jaw of Torynobelodon compared to Platybelodon grangeri.]()

Lower jaw of Torynobelodon compared to Platybelodon grangeri. From Barbour, 1931

![Lower tusk of Torynobelodon.]()

Lower tusk of Torynobelodon. From Barbour, 1929

![Purely conjectural reconstruction of the lower jaw of Torynobelodon, based on the curvature of the lower tusk.]()

Purely conjectural reconstruction of the lower jaw of Torynobelodon, based on the curvature of the lower tusk. From Barbour, 1929

![Hypothetical reconcostruction of Torynobelodon grubbing for water plants.]()

Hypothetical reconcostruction of Torynobelodon grubbing for water plants. From Barbour, 1929

![Lower jaws of Serbelodon.]()

Lower jaws of Serbelodon. From Osborn, 1933

![OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA]()

Skull and jaw of Gomphotherium from northern California, on display at the Lawrence Hall of Science, UC Berkeley.

![]()

Lower jaw (front) and skull (back) of Tetrabelodon. Image from Wikipedia.

![]()

Lower jaw of Archaeobelodon from Europe. Image from Wikipedia.

![63664220]()

Reconstruction of Stegotetrabelodon. It has a relatively short jaw with very long bottom tusks. By Mauricio Anton, from the book “Evolving Eden”

Complicating the matter is another subset: the spoonbill mastodons. These were shovel-tuskers who had no lower tusks. The flagship species is a somewhat enigmatic animal called Gnathobelodon:

![Lower jaw of the spoonbill mastodon Gnathobelodon thorpi]()

Lower jaw of the spoonbill mastodon Gnathobelodon thorpi. From Barbour & Sternberg, 1935

![Lower jaw and upper tusk of the spoonbill mastodon Gnathobelodon thorpi]()

Lower jaw and upper tusk of the spoonbill mastodon Gnathobelodon thorpi.

![Reconstruction of the spoonbill mastodon Gnathobelodon thorpi scooping pondweed.]()

Reconstruction of the spoonbill mastodon Gnathobelodon thorpi scooping pondweed. From Barbour & Sternberg, 1935

Joining the spoonbill clan is Megabelodon:

![Lower jaw of the spoonbill mastodon Megabelodon from Nebraska.]()

Lower jaw of the spoonbill mastodon Megabelodon from Nebraska. From Barbour, 1934

![Mounted skeleton of the spoonbill mastodon Megabelodon, apparently spooked by a sabertooth cat.]()

Mounted skeleton of the spoonbill mastodon Megabelodon, apparently spooked by a sabertooth cat. From Barbour, 1934

![Reconstruction of the spoonbill mastodon Megabelodon feeding on leaves and twigs.]()

Reconstruction of the spoonbill mastodon Megabelodon feeding on leaves and twigs. From Barbour, 1934

Next in the spoonbill parade is Eubelodon from Nebraska :

![]()

Skull of Eubelodon morrilli from the late Miocene of Nebraska. From the University of Nebraska Lincoln Libraries Image and Multimedia Collections.

![]()

Skull of Eubelodon morrilli from the late Miocene of Nebraska. From the University of Nebraska Lincoln Libraries Image and Multimedia Collections.

And Choerolophodon from the Aegean region:

![Skull of the spoonbill mastodon Choerolophodon from the late Miocene of Greece.]()

Skull of the spoonbill mastodon Choerolophodon from the late Miocene of Greece. From Konidaris et al, 2014

The structure of Megabelodon’s jaw clearly indicates it evolved that way. But how do we know it wasn’t simply a pathology? That some traumatic injury caused it to lose the lower tusks and the bone grew back in a funky manner? A little thing called multiple specimens:

![Lower jaws of different species of Megabelodon. The left specimen is from South Dakota, while the right is from Nebraska.]()

Lower jaws of different species of Megabelodon. The left specimen is from South Dakota, while the right is from Nebraska. Barbour, 1934

![]()

Skull and jaw of Megabelodon (i believe the same one from Barbour’s paper) on display at the Geology Museum at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. Image by flickr user James

But of course, when dealing with such a large and diverse group, there’s bound to be at least one outlier. Enter this gomphothere on display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science:

![]()

Skeleton of a gomphothere with a peculiarity in its lower jaw. From flickr user James Brian Clark.

A pdf about the history called it “Amebelodon phippsi”. However, i contacted the museum and was told it was reclassified as Gomphotherium productum. There is one problem however: it doesn’t have any lower tusks. All the images of Gomphotherium productum i can find clearly show tusks in the lower jaw. Was this specimen just found without the lower jaws? Or were they never there to begin with? The jaw appears to be symmetrical, which rules out pathology. Could it be that this is another specimen of Megabelodon? It does bear some similarities to the jaws we saw above.

Anyway, just what were shovel-tuskers doing with their jaws? The traditional view was that they used their tusks to either dredge water plants or dig up roots. I once heard it suggested that Gnathobelodon scooped aquatic plants while the shovel-tuskers, with their solid lower tusks, “attacked firmer soil”. The hypothesis for Megabelodon (at least the “main” specimen from Nebraska) was that the end of the lower jaw supported a thick gristly pad that may have been used to grab leaves and twigs. Some work has been done on Platybelodon and Amebelodon. The study looked at the wear on the lower tusks and found that rather than plowing wetlands for lunch, they may have been using their tusks to cut grass and peel bark from trees. Perhaps their tusks were Swiss army knives, used for a variety of functions. More study is needed.

For example, i think paleoenvironmental data should be taken into consideration. Microwear analysis of the teeth of Choerolophodon suggested it lived in an open, arid habitat. At the same time shovel-tuskers of the genus Gomphotherium lived in the wetter and more forested lands of Germany. Neither invaded the others range. Eubelodon lived at a time when the vast sea of grass known as the Great Plains were taking hold. Perhaps the loss of tusks and shortening of the jaw were a response to dwindling forests and decreasing water sources. Maybe some of the shovel-tuskers did use their jaws on trees in some way. This in turn could be why they mostly went extinct by the late Miocene. The riddle of the shovel-tuskers has yet to be solved. Chief among the questions is: if these tusk and jaw arrangements evolved to browse leaves and cut grass, why the elaborate set up? Mammoths, mastodons, and modern elephants were/are able to feed on these food sources with just their trunks. Since the ancestors of these animals already had somewhat elongated jaws with lower tusks, did they just end up developing what they already had? So as you can see, a lot of work remains to be done. Truth be told I don’t know why more people aren’t studying these truly awesome and fascinating animals.

- Sabertooth Salmon

Saber teeth have been found in four groups of mammals: creodonts, nimravids, thylacosmilids, and true cats. Saber like teeth are also known in gorgonopsids, ancient mammal-like reptiles. But the Cenozoic found yet another group to slap these stunning teeth on: salmon. Salmon are perhaps the best known food fish. They are also well known for their lifestyle. Salmon live in the sea but return to freshwater streams and rivers to spawn (the same one where they themselves were born).

Oncorhynchus rastrosus was undoubtedly the king of salmon. It grew to 9 feet long. So not only did it sport the characteristic saber teeth, but it was pretty big as well. I wish I could say more, but fish are outside my area of “expertise”

- Gigantopithecus

King Kong is my all time favorite movie. Which one you may ask? Both of them. I don’t try to argue which one is better. They both serve different purposes, have different methods of conveying their themes, and are both reflections of their times. The ‘76 version just sucked ass. Needless to say I am looking forward to Legendary’s “Skull Island”, although I not entirely sold on setting it in the 1970s. I feel having it set in the ‘30s added to the sense of adventure and to the challenge of combating giant prehistoric monsters. Look no further than the climax of the ’76 version. Instead of a fierce and thrilling battle atop the Empire State Building, Kong was dully gunned down by helicopters armed with mini-guns. Does Skull Island seems as frightening and foreboding if your men are armed with assault rifles, modern hand grenades, and machine guns? I don’t think so. But we will have to wait and see what the film makers have planned.

![BOO! Watching helicopters sit there and pump Kong full of lead is boring! Copyright Universal.]()

BOO! Watching helicopters sit there and pump Kong full of lead is boring! Copyright Paramount Pictures.

Kong is usually thought of as pure fantasy. But the fossil record, as usual, shows fact is stranger than fiction. In 1935 a German scientist bought a fossil tooth in a Chinese apothecary. The Chinese believe fossils to be the bones of dragons and as such grind them up for medicinal purposes. The tooth proved to be that of an ape. Based on the size of the tooth, it must have been one huge ape. He named it Gigantopithecus blacki, the “gigantic ape”. Since that initial discovery 3 lower jaws and 1300 teeth have been found and that is why Gigantopithecus is such a mystery.

![Life sized model of Gigantopithecus on display at the San Diego Museum of Man]()

Life sized model of Gigantopithecus on display at the San Diego Museum of Man

![Cast of the lower jaw of Gigantopithecus, with my pocket knife (5 inches closed) for scale. Taken at the San Diego Museum of Man]()

Cast of the lower jaw of Gigantopithecus, with my pocket knife (5 inches closed) for scale. Taken at the San Diego Museum of Man

Teeth and jaws can be helpful in understanding taxonomy and diet, but little else. Not even a partial skull has turned up. So we have to make do with what we have. Based on the dimensions of the jaws, it is estimated (key word being estimated) that Gigantopithecus would have stood 6 feet tall on all fours, 9 feet tall on its hind legs, and weighed 1100 pounds. This makes Gigantopithecus the largest ape and largest primate by far. Of course without postcranial bones this size estimate is far from perfect. The large, robust teeth suggest it ate very tough vegetation; bamboo has been suggested as a staple. It was obviously too heavy to live in the trees and would have had to live on the ground. Without any limb and foot bones we have no idea how it walked. Anthropologist Jeff Meldrum has suggested that Gigantopithecus was bipedal since the classic ape knuckle walk would not work with an animal of that size. This is often brushed off as preposterous and just another hair brained idea to support his belief in Bigfoot. But how do you know? Some modern great apes knuckle walk, but they don’t even approach Gigantopithecus in size. It was over 7 times the weight of a chimpanzee and almost 3 times heavier than a gorilla. Many species of ground sloths equaled and exceeded the weight of Gigantopithecus, but they aren’t built like apes. The knuckle walking Chalicotherium was twice the weight, but does it serve as an appropriate analogue? Again, without any bones of the limbs and hands/feet, how Gigantopithecus got around will perhaps be the biggest enigma of all.

Dating Gigantopithecus has been difficult as well. Right now the youngest dates for the big ape are a little as 100,000 years ago. This would seem to overlap with the early human Homo erectus. Did they cross paths? Hard to say. Gigantopithecus kinda just disappears from the fossil record. Did Homo erectus have a hand in its extinction? Or was it competition from early pandas over access to bamboo? It seems we know more about King Kong than the real McCoy.

- Deaodon

Predatory dinosaurs get all the hype. Jack Horner once said in a discussion at the Natural History Museum in London: “I’d rather be locked in a room with 4 lions and a tiger than one little Velociraptor. Because that Velociraptor will probably eat half of me before it kills me.” Evidence? Why Jurassic Park of course (ok he didn’t say that explicitly, but seriously, where else could such hyperbole come from?)! In the film series Velociraptors are huge, super fast, hyper intelligent killing machines that can eat a cow in 10 seconds and run as fast as a cheetah and leap 15 feet into the air and be lethal at 8 months old and AAAAAAAHHHHHHH!!!1! If only. Never mind the fact that I could take out the real Velociraptor with my pocket knife; dinosaur behavior is a very hard nut to crack. Even more difficult is saying with any certainty if they were as savage as their Hollywood counterparts. There is evidence that T. rex was pretty nasty, but raptors are harder to come by. So let’s meet an animal who was every bit the tyrant people think Velociraptor was: The Hell Pig.

The official name is Entelodont. These animals are called pigs, are related to pigs, but are their own distinct group. Entelodonts lived from the latest Eocene through to the early Miocene. Their fossils are known from Europe, Asia, and especially North America. They were very robust, not particulary fast (due to the fused nature of their lower legs). These animals were built for power. They possessed huge heads with massive jaws and teeth. And those skulls are how we know they were so vicious. Many entelodont skulls have been found with fractures and bite marks. Aside from matching up the bite marks, the only animal alive at the time place that could do that kind of damage to an entelodont… was another entelodont. Looking at the skull it is easy to see it was built to savage and get savaged back. The canines are thick and robust. The flaring cheek bones likely helped to project the eyes. Their modern relatives, the pigs are similarly equipped. The wide cheek bones and various warty calluses- the things people think make them ugly- help protect their eyes and faces when males fight each other. Hey whatever gets the job done.

![The entolodont Archaeotherium scares away a pair of the primitive dog Hesperocyon from a watering hole. Oligocene of western North America. By Mauricio Anton from the book "National Geographic: Prehistoric Mammals"]()

The entolodont Archaeotherium scares away a pair of the primitive dog Hesperocyon from a watering hole. Oligocene of western North America. By Mauricio Anton from the book “National Geographic: Prehistoric Mammals”

Now onto the star: Daeodon. This guy was the largest of the Entelodonts. It stood 6 feet tall and weighed as much as a modern bison.

![]()

Daeodon compared to a carnivorous dinosaur. While most people would think the dinosaur would win, it’s really anyone’s guess (entelodonts certainly have the jaw power and attitude to give dinosaurs it’s size a run for their money). From the Carnivora Forum

Its massive skull was almost 3 feet long. The size of many tyrannosaur skulls (and only 1 foot shorter than the average T. rex skull).

![]()

The massive skull of Daeodon on display at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Image from Wikipedia.

The teeth are monstrous. In fact Daeodon means “dreadful teeth”. And bones of the contemporary herbivores show just how dreadful they were. The classic example is a humerus (upper arm bone) of a calichothere from the Agate Springs area in Nebraska, representing the bottom half of the bone. It bears several bite marks that match the teeth of Daeodon. Not only that, but the bone was bitten in half. We’re talking about an animal the size of a horse. And its bone was bitten in half.

![]()

Humerus of the calichothere Moropus that was bitten in half by a large carnivore. The marks are a great match for the tooth of Daeodon. Photo by Alton Dooley.

Whether it was killed or scavenged may be a moot point. Daeodon was big enough, powerful enough, and probably fast enough to dine on whatever it wanted. Entelodonts may have been like some bears today, using their size and strength to steal kills from other carnivores. While thought to be primarily carnivores, the heavily worn teeth of entelodonts show they ate just about anything they could get a hold of. They had the teeth and the jaw power to kill, crush, break, and grind. How many dinosaurs can claim that?

![]()

Fleshed out model of Daeodon on display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. Picture by Flickr User Michael.

Daeodon was not only the largest entelodont but it was also the last. It appears super sizing didn’t work out for them in the long run. Whether it was competition from new predators like bear-dogs and true dogs or climate change, one of the nastiest brutes to ever walk the earth had bitten one last thing: the dust.

- The Giant Ground Sloth

Giant ground sloth is a common name seen in discussions about the Pleistocene. But the name really only applies to a few species. This next animal is not only giant in stature, but also the original giant prehistoric beast. At about the same time mammoths were being pulled from the Siberian permafrost a very different extinct giant was found in Argentina. It was unlike anything known at the time. To early naturalists, it looked out of this world. Here they had an animal with a wide pelvis even for a creature of that size. The rib cage flared out at the bottom to house a large gut. It had long arms and stout legs. It walked on its knuckles and the sides of its feet to protect enormous claws. The skeleton showed it could rear up on its hind legs like a bear. Its teeth have no enamel, so they were forever growing. A great trough in the lower jaw suggests it had a long tongue like a giraffe. Even to this day this animal and it’s kin are some of the strangest animals that ever lived on this planet.

This animal is Megatherium; the “giant beast”. Back before dinosaurs stole the spotlight, Megatherium and other Pleistocene wierdos from South America dominated museums and depictions of the prehistoric past. Skeletons of Megatherium and Glyptodon were the centerpieces of the most prestigious institutions in Europe. People marveled at this strange monster that towered over them. Scientists deduced that it was related to modern tree sloths. Though just looking at it no one could make that connection. Megatherium even factored into Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. Looking at the fossils of this giant sloth compared to its living cousins helped illustrate extinction, that one species dies out while another related species lived on. But Megatherium’s days were numbered. Once dinosaurs started emerging as skeletons, the giant mammals of the past were overshadowed. It was all about who was bigger, scarier, toothier… Mammals having to play second fiddle to dinosaurs remains to this day.

![]()

Skeleton of Megatherium americanum stands tall and proud in the Natural History Museum, London. From Wikipedia

Megatherium lives up to its common and scientific names. Weighing five tons and able to stand 13 feet tall it was one of the largest species in Pleistocene South America. Megatherium always appears in depictions of the time. Usually it is shown resting on its haunches, pulling down branches with its claws and feeding with a long tongue (though I have heard somewhere that the tongue thing may not hold much water). Megatherium lived mostly in South America. I have heard a few reports in Central America. But there is one report that has caught my attention. According to Berkeley’s online database, there a vertebra from the Pleistocene of Santa Barbara County. The id: Megatherium sp. This could be big. This could greatly extend the range of Megatherium, showing it made it into North America along with other megafauna from the south. Hell, THE giant ground may have lived on the Central Coast! But we may never know though, at least for a while. I thought the vertebra might be a good first research project for me. So I wrote to Berkeley, even asking if they could send me a photo of the specimen, so I could determine whether or not I should drive 5 hours up there to investigate. I never heard back. I guess a prestigious institution such as Berkeley can’t be bothered with amateurs like me. Only “true” scientists allowed!

Ok, that’s a bit harsh. I of course have no idea why my efforts to contact Berkeley are a one way conversation. But it is frustrating when you are trying to make progress as an citizen scientist. And especially when you are trying to verify or debunk a potentially important fossil. And when that fossil concerns a species with a rich and intriguing history as Megatherium. Megatherium is every bit a cornerstone of the history of paleontology as Tyrannosaurus rex, Archaeopteryx, and Protoceratops. Perhaps I can help bring him back to his rightful glory.

![A beautiful reconstruction of Megatherium (joined by the glyptodont Panocthus) on the pampas of Pleistocene South America. From the (ancient) Time-Life Nature Library: South America]()

A beautiful reconstruction of Megatherium (joined by the glyptodont Panocthus) on the pampas of Pleistocene South America. From the (ancient) Time-Life Nature Library: South America

- Megalodon

Growing up, there were few things I loved watching more than those old dinosaur shows by Midwitch Entertainment. They were fun, well put together, and even informative now and then. But what stuck with me most was the music. While quite clearly 80s in style, they were nonetheless very evocative and really drew me in to the narrative. These qualities were perhaps most present in a song called “The Ice Age”. It was used to bring a particularly mysterious feel to the subject at hand (the woolly mammoth, Antarctic dinosaurs, and most fittingly, the Loch Ness Monster). I tell you this because this haunting tune enters my mind whenever I think about a shark that could bite Jaws clean in two. I’m of course talking about Megalodon.

This leviathan of prehistory almost needs no introduction. It has become so well known in recent years no thanks to modern B-movies and one truly dumbass Discovery Channel show (which purported to show Megalodon was still alive. It was a farce but because they presented it so seriously people actually believed it). But it has become one of the most famous mega-predators in prehistory. Despite all that has been written and done about Megalodon, we actually don’t know much about the animal proper. Being a shark it’s skeleton was composed of cartilage. Cartilage is softer than bone and thus never fossilizes (except under the most exceptional of circumstances). All we have are its teeth and a few vertebra. Sharks are contantly shedding and replacing their teeth. A single shark could go through up to 30,000 teeth in its life time. So luckily we have lots of Megalodon teeth to work with.

![Teeth of Megalodon from southern California at the San Diego Natural History Museum]()

Teeth of Megalodon from southern California at the San Diego Natural History Museum

The teeth themselves are unholy in size. They average 5-6 inches long and are very thick for shark teeth. Looking at a Megalodon tooth, I am reminded of the sharktooth weaponry from the ancient Pacific. If Megalodon were still alive today, I can easily see those people using its teeth as spearheads and hand axes. But back on topic. Scientists have found a correlation between the size of a tooth and the size of the shark it came from. Using this formula, the best estimate for Megalodon is 50 feet long. The biggest killer shark today, the great white, rarely reaches 20 feet. I’ll let that sink in for a minute.

![Life size model of Megalodon at the San Diego Natural History Museum. The model measures 34 feet long, a female according to them.]()

Life size model of Megalodon at the San Diego Natural History Museum. The model measures 34 feet long, a female according to them.

Given its great size Megalodon likely fed on large marine mammals. Whales appear to have been the main targets. Many a fossil whale bone has been found with bite marks consistent with Megalodon teeth. In fact some whale bones have been found with Megalodon teeth embedded in them. Now whales weren’t always the giants we know today. During the Miocene most measured 20-30 feet long. But when they started getting bigger in the Pliocene it appears Megalodon was able to keep pace. According to a National Geographic documentary, a whale found near Santa Barbara (Central Coast, yay!) had the tip of a Megalodon tooth in one of its bones. The hitch: this whale was the size of a modern fin whale, outweighing the mega-shark by 25 tons. Whether it killed or scavenged the whale is up for debate. There is no reason to think Megalodon was incapable of attacking a whale of this size.

![A fossil whale rib bearing the tooth marks of Megalodon. In the old fossil halls at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History]()

A fossil whale rib bearing the tooth marks of Megalodon. In the old fossil halls at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History

Megalodon terrorized the seas for over 13 million years. There was nothing it couldn’t at least take a bite out of. So why did such an awesome predator die out? Current thought is it was a combination of climate change and prey. As the world’s oceans became cooler during the Pliocene Megalodon would have had to stay in warmer waters. Whales are thought to have adapted by developing their characteristic layers of blubber and migrating to colder waters. Without a consistent, year round food source, Megalodon starved into extinction. I’m pretty sure a lot of people, especially Jesse Cox, thank their lucky stars every day that the Godzilla of sharks is no longer with us.

- Livyatan

For decades Megalodon was thought to be the undisputed king of the seas. It was perhaps the mightiest ocean predator that ever lived. Modern orcas are smaller and while able to prey on adult whales they need pack hunting behavior to achieve this. Sperm whales are the same size, but they only have lower teeth and feed on squid. The ancient whale Basilosaurus was as long but not as bulky, and probably didn’t tackle especially large prey (hell it was biggest animal on earth at the time). Megalodon was unchallenged. That is until 2008 when paleontologists in Peru found a whole new monster.

It was a whale, a sperm whale in fact. But it wasn’t like its modern cousin. Its 9 foot skull was much more robust. Not only were its teeth much more massive, but it had upper and lower teeth. This wasn’t some oversized squid sucker. This thing meant business. The scientists were Herman Melville fans and decided there was only one name worthy of this beast: Leviathan melvillei. Leviathan is not only a name of a Melville novel, and is not only a commonly used descriptor for giant marine monsters, but is also the name of a legendary monster in the Old Testament. Leviathan was lord of the seas and was the most feared creature in creation. Its immense size meant nothing was safe from its rapacious appetite. What better name for a whale like this? Unfortunately, the name didn’t last. Turns out some guy in the 19th century used the name Leviathan on a mastodon tooth. So the authors had to change the name to Levyatan (the original Hebrew spelling). This is one of those instances where I feel the rules of science can just go eat a dick. The name was used on something that already had a name therefore it has to stick and cannot be used ever again. Leviathan was a much better name, so much more fitting. But that is just my opinion.

![]()

Reconstructed skull of Livyatan melvillei. By deviantart user Juandarkgraff

Livyatan is thought to have been a top predator. In fact many of the sperm whales during the Miocene were thought to be “raptorial” macropredators. These Miocene sperm whales had functional upper and lower teeth, which makes scientists think they were preying on stuff beefier than squid and fish. They were probably feeding on marine mammals in addition to large fish like modern orcas. There were many species of dolphins, pinnipeds, and sea cows to choose from. They may have even preyed on juvenile whales, or maybe even hunted cooperatively to take on adult whales. While all this is up for debate, we know it certainly had the hardware to do so. A study found that in addition to functional upper teeth and powerful jaws, these ancient sperm whales (or at least the species studied, including Livyatan) had unique knobs in their upper jaw. Analysis of these growths shows they would have acted as buttresses to reinforce the jaw; reinforced specifically during a strong up/down action. In this case, the high forces produced by a powerful bite. It should be pretty obvious that these whales were preying on things that required enormous bite force to subdue.

![Skull of the sperm whale Acrophyseter, highlighting the bony buttresses that reinforced its teeth.]()

Skull of the sperm whale Acrophyseter, highlighting the bony buttresses that reinforced its teeth. From Lambert et al, 2014

So we had 2 giant predators prowling the coast of South America 12-13 million years ago (the other being Megalodon). How they coexisted is yet to be determined. Right now we just have the one specimen. But right now that one specimen is enough to fire the imagination. This was potentially a contender for largest predator in the history of the planet. If I ever came face to face with the gaping, spike-toothed maw of a real life sea monster, I think I’ll take my chances with those cute little mosasaurs.

![]()

Livyatan in the process of attacking a baleen whale

- Woolly Mammoth

When I was two, my family took a visit to the Royal British Columbia Museum in Canada. I immediately fell in love with their model of a woolly mammoth. We would see some of the museum, then go back to see the mammoth. We would see some more of the museum, then go back to see the mammoth. My parents inform me they only got me to leave by buying me a poster of the big lug, which is still on my wall to this day. It’s part of why I am who I am and why I pursue paleontology. I last saw him in 2006. He still remains the best prehistoric model I have ever seen. You can go into the next gallery and see bear and elk that don’t look any more lifelike.

![]()

No photo, not matter how beautiful and well taken, cannot match the awe and power of seeing this model in person. From Wikipedia

Woolly mammoths are among my top favorite prehistoric animals. So you may be a bit surprised to learn that I’m actually not writing anything about it. I love it dearly, but let’s face facts. The woolly mammoth is not only the face of the ice age but it is one of the very icons of prehistory. Entire books, documentaries, and articles have been written about it. Not to mention it appears in just about every discussion of the ice age. Thus there is nothing more I can really add. Which is good because we are only halfway through and anything that reduces the amount of typing I have to do is welcome!

- Elasmotherium

While we are on the subject of woolly giants, let’s explore a far less known but perhaps stranger beast. Now the woolly rhino is often depicted alongside the all too familiar mammoth. This is the species Coelodonta antiques. Remains have been found all across northern Eurasia, including mummified remains in a Polish tar pit. But he was not the only rhino running around. There was another behemoth that was bigger in every way. We are talking about Elasmotherium.

I use behemoth a lot to describe big animals, but Elasmotherium is one of the ones actually deserving of that title. It rivaled elephants in size, standing 7 feet at the shoulder and tipping the scales at 4-5 tons. Only mammoths and a couple giant sloths were bigger. Elasmotherium is not only famous for its size.

![]()

Massive skeleton of Elasmotherium caucasicum in the Azov historical and archaeological and paleontological museum-reserve. From Wikipedia

To understand the second reason, we need to look at how rhino horns work. Rhino horns are not made of bone but are made of keratin. This is the same material as your fingernails. A rhino skull has a rough built up base of bone that serves as an anchor for the horn. This is how we can estimate the size of the horns on extinct rhino. We know Diceratherium has two small horns because its skull has two small bases. We know Aphelops had no horn because its skull doesn’t have a base. Elasmotherium is different matter.

You see, rhinoceros means “nose horn”. Most rhinos follow this rule. But Elasmotherium was a hipster. He didn’t want to be “mainstream” and follow the “crowd”. His horn wasn’t on his nose. It was on his head:

![]()

Skull and reconstructed horn of Elasmotherium at the Natural History Museum, London. From Wikipedia

We know this because the dome resembles the roughened base. This makes Elasmothering look like he’s wearing a helmet (or like a pachycephalosaur).

![]()

Skull of Elasmotherium, prominantly showing the bony dome that served as the base of the horn. From Wikipedia

Based on the size of the base, the horn must have been huge. Most estimates put the horn at 6 feet long. That would skewer any would be predator. But this is really all just a round-a-bout way of showing you that unicorns are real. Just instead of beautiful horses they were giant, hairy, probably smelly rhinos…

![]()

Life reconstruction of Elasmotherium. By deviant art user WillemSvdMerwe

- Paraceratherium

People, it would appear, are easily cowed by size. They are only awed by the biggest; they only care about the biggest. We see this problem in the public perception of paleontology, where dinosaurs rule. To the public, dinosaurs represent the biggest, weirdest things in nature. It doesn’t help that in the public arena the most extreme mammals can barely compete with the most basic of dinosaurs. I have already talked about how mammals once ruled the museums. Here we will meet one of the most extreme mammals. It is extreme for how big it is. It was found when Roy Chapman Andrews and his crew were scouring the Gobi for fossil treasures. While talking with local tribesmen, they were told of a place where they could find bones “big as a man’s body”.

The bones belonged to a type of rhino. But it was bigger than any rhino known, including the aforementioned Elasmotherium. In fact, only mammoths were on the same scale. The called the animal… well its name is a little confusing. Throughout my life I have heard it referred to as Balucatherium, Indricatherium, and Paraceratherium. The last one seems to have stuck the most so we’ll go with that. Paraceratherium lived during the Oligocene epoch (and very earliest Miocene), 34-23 million years ago. It is mostly known from Mongolia, although some remains have been through ought Asia and even into Eastern Europe. It resembled a giant cross between a rhino and a giraffe.

![Life-size model of Paraceratherium at the California Academy of Sciences]()

Life-size model of Paraceratherium at the California Academy of Sciences

Paraceratherium is the largest land mammal known. It is estimated to have stood 17 feet at the shoulder and weighed between 15 and 20 tons. But these estimates are problematic due to a lack of complete specimens (Seems all the paleontology in Mongolia is completely fixated on the dinosaurs. Maybe that’s why Andrewsarcus is only known from a skull. No one is even looking for the rest). Now Paraceratherium seems like a lightweight compared to dinosaurs. But not only is size not everything, but have you ever stoped and wondered why mammals are not as big as dinosaurs? Someone in the Royal Tyrrell Museum’s speaker series has some ideas. I’ll just let her explain it:

![Indricotherium, an extinct herbivore mammal from the Oligocene]()

(Paraceratherium skeleton at the Moscow Paleontological Museum. From flickr user cazfoto)

Basically nothing came close to Paraceratherium’s size until the mammoths of the Pleistocene. Now I don’t know what may have spurred their gigantism (I haven’t read Prothero’s book). Because of its record breaking status, Paraceratherium is perhaps doomed to be mentioned mostly in countdowns of extreme mammals.

![A herd of Paraceratherium crosses the grasslands of Oligocene Mongolia. By Mauricio Anton, from "National Geographic: Prehistoric Mammals"]()

A herd of Paraceratherium crosses the grasslands of Oligocene Mongolia. By Mauricio Anton, from “National Geographic: Prehistoric Mammals”

- Palorchestes

Back to the Land of Oz for us. Remember way back when I mentioned something in the Australian Pleistocene that is often thought of as being a ground sloth analogue? I was reffereing to this guy: Palorchestes

When Palorchestes was first described by Richard Owen he thought it was a giant kangaroo. So he named it Palorchestes which means “great leaper”. But Palorchestes was far weirder than most kangaroos. Owen described the species from the Pleistocene, Palorchestes azael. We didn’t get our first good idea of what the hell it was until the discovery of the Alcoota bonebed. Alcoota dates to around 8 million years ago and in addition to fossils of giant wombat-like animals, huge birds, and crocodiles, scientists found fossils of a new species of Palorchestes. Dubbed Palorchestes painei, fossils included a complete (albeit crushed) skull. This skull didn’t look like any kangaroo skull. In fact, it looked more like a tapir.

![Reconstruction of the pleistocene species Palorchestes azael. From]()

Reconstruction of the pleistocene species Palorchestes azael. From

It is thought that Palorchestes had a tapir-like trunk because, like tapirs, it has a heavily retracted nasal cavity:

![]()

Reconstructed skull of Palorchestes azael.From Museum Victoria.

But that is where the tapir similarity ends. Palorchestes had very robust limbs like a bear, ending in long sharp slaws like those of a ground sloth. Palorchestes teeth showed it fed on very abrasive vegetation. In fact, those teeth combined with the claws and muscles has led paleontologist Tim Flannery to call them “tree wreckers”. Perhaps a big part of their diet was tree bark. While more fossils of both species (Especially the Pleistocene one), like all Australian megafauna there is so much we have to learn about one of the strangest chapters in the history of life. Australia has a very poor fossil record when compared to the rest of the world. It is thought that this is the case because unlike some of the well known, very fossiliferous localities around the world, Australia has undergone very little geologic upheaval. Not only are new sediments not being exposed by uplift, faulting, and erosion; but without runoff from mountains and hills little new sedimentation takes place. But what Australia has generously given us thus far is one of the most fascinating tales of evolution. Animals weird and bizarre even by the standards of the fossil record evolving in isolation to produce animals like no others. Palorchestes is one of the strangest, but it is by no means the only one.

- Meiolania

The Pleistocene of Australia was once thought to be ruled by reptiles. In fact, scientist Stephen Wroe once described it as “a b-grade rerun of the Age of Reptiles”. We now know this isn’t true (not only that, but I think Cerrajon is a better candidate for that description), that the Australian Pleistocene was a unique mixture of mammals and reptiles that was unique in earth’s history. The “reptilian domination” focused mostly on predators. But there was another odd reptile who added another twist to the surreal fauna.

Meiolania was a giant tortoise who belonged to an extinct subfamily, the Meiolanidae. These turtles were first thought to have first appeared in the Oligocene in Australia. But then Meiolanids were discovered in Argentina, one of them dating to the Eocene. This suggests they occurred before the breakup of Gondwana when Australia and South America were still connected. Some specimens of this group have been found on islands like Vanuatu, Lord Howe Island, New Caledonia, and possibly Fiji. These animals must have arrived by rafting. Meilanids are characterized by their spiky heads and heavily armored tails.

![]()

Skeleton of Meiolania on display at the American Museum of Natural History. From Wikipedia

![]()

Rear view, offering a better look at the nasty looking tail club. From Wikimedia

Meiolania was the largest, stretching 8 feet long and probably weighed at least a ton. This makes it the second largest terrestrial turtle/tortoise (surpassed only by Megalochelys atlas). The horned skull and tail club feel reminiscent of the ankylosaurs. But with their domed shells and armored tails they remind me of South American glyptodonts. Now Meiolania wasn’t alone during the Pleistocene. In Queensland it was joined by its smaller cousin Ninjemys. And yes, that name means “ninja turtle” and yes it was meant to honor who you think it does. Like the glyptodonts they resemble, they were likely almost immune to attack from predators.

These giant tortoises succumbed to the same extinction that claimed Australia’s megafauna 50,000 years ago. The two sides butting heads are humans and climate change. Climate change posits that at this time there was a massive climate shift in Australia. The climate became hotter and drier. This wiped out the plants that the mega herbivores fed upon. Without mega herbivores to prey on the mega predators followed them into oblivion. Not so says the human crowd. They argue that it doesn’t make sense that these animals survived numerous climate changes before only to succumb to this one. They argue that over hunting by humans must have been the culprit. One study done on the fossil teeth of wombats and eggs of emus shows there was a huge crash in plant diversity. They argue that the abruptness can only be explained by human intervention. Humans are thought to have entered Australia ~50,000 years ago. The timing is suspicious but alone is not enough. It is argued that the sudden crash in plant diversity was caused by the Aboriginal practice of burning the bush. This is when the land is deliberately set on fire, not just to flush out game but to also make the land more suitable to the animals they like to hunt (this practice isn’t exclusively Australian). How can a population of 3 ton wombat-like animals (Diprotodon) hope to survive if humans are burning away their food?

The debate is fierce and there is no hope of it being resolved anytime soon. Too few sites that offer insight into this crucial time period have been uncovered. Was it just one factor or was it a combination of both? Whatever it was Meiolania managed to dodge it for a while. What are known as relict populations survived on the off shore islands. That is until they were settled by humans. Island ecosystems are especially vulnerable to change. With limited habitat supporting small populations and nowhere to run, it was easy for pioneering humans to wipe them out. In Vanuatu meiolanid bones have been found in a 3000 year old midden. It would have been fantastic if this lone survivor of the Pleistocene extinction had survived to modern day. Hell if any of the megafauna of Australia had survived. The wholly unique animals of Pleistocene Australia continue to call to me. While I wish the megafauna of the Americas had survived, Australia still captures my imagine the most. Perhaps if time travel is ever invented, and I could only go one place, it would the ice age in the strange and wonderful Land Down Under.

- Kubanochoerus

Pigs are ubiquitous members of any farm. They not only make those funny oinking sounds, but also provide us with delicious bacon. Thanks to humans pigs span the globe. Many break free and become feral hogs, where they wreak havoc on the local ecosystem. In fact I have seen some people get surprised when I tell them pigs are not natives and instead are introduced invaders. Pigs are one of the ultimate survivors. They can and will eat anything, they reproduce like crazy, and are strong and fierce enough to live free from any natural predators. These pigs were in turn domesticated from wild boars, perhaps as early as 10,000 years ago.

So it should be no surprise then that pigs have a long and successful run through the fossil record. Of course back then there were large and powerful predators like sabertooth cats, bear-dogs, and hyenas that could take them (at least on occasion). Despite this pigs managed to create a diversity of forms. The strangest has to be Kubanochoerus gigas. Hailing from the Miocene of Asia, it was a hefty hog approaching the size of a cow. But it is most famous for the horn on its skull. This long horn is present only on the males, so it was probably used by males for fighting each other. So not only did rhinos try to be unicorns, but apparently pigs took a whack at it as well.

![Skull and fleshed out reconstruction of Kubanochoerus gigas. By Mauricio Anton, from the book "Mammoths, Sabertooths, and Hominids"]()

Skull and fleshed out reconstruction of Kubanochoerus gigas. By Mauricio Anton, from the book “Mammoths, Sabertooths, and Hominids”

- Merycochoerus

The Cenozoic era is full of migration stories. Animals spreading this way and that. There were many faunal exchanges between the old world and new. And yet despite this many regions managed to house unique groups found nowhere else. One such family was the oreodonts. These cousins of sheep and pigs thrived in North America from the middle Eocene all the way to the late Miocene. They were at their peak during the Oligocene, reaching a diversity unrivaled by any other group at the time. Probably the king of them all was Merycochoerus.

Merycochoerus was a species that lived from the middle Oligocene to the early Miocene (29 to 20 million years ago). It was 900 pounds in weight, making it one of the largest animals in the mid-late Oligocene. What makes Merycochoerus unique is that it looks like a mash up of a pig and a hippo. Observe:

![Skull of Merycochoerus from the Oligocene John Day formation, Oregon]()

Skull of Merycochoerus from the Oligocene John Day formation, Oregon

Oreodonts were wildly successful during the Oligocene but lost steam after that. They stuck around until the late Miocene before finally going extinct. What happened? One thought is that as browsers oreodonts were unable to adapt to the continuing expansion of grasslands. They thrived in the woodlands of the Oligocene, but the Miocene saw the development of the savannah. Horses and other animals adapted by evolving longer legs, hooves sturdy enough to run on open ground, and high crowned teeth designed to grind tough grass. But oreodonts stuck with their shorter legs and low crowned teeth. Perhaps oreodonts, once the most successful groups of mammals in North America, went extinct out of stubbornness.

![]()

Skeleton of Merycochoerus from the Miocene of Nebraska. From flickr user Mrs Pugliano

- Sivatherium

The giraffe is a strange if not majestic animal. It is the tallest living animal, with males approaching 16 feet tall. They have bony knobs on the top of their heads. They slurp up leaves with blue-black tongues 18 inches long. Because of their long necks and legs they have to awkwardly squat down to get a drink of water. Amazingly though, it uses those long legs to run 20 mph. Giraffes were thought to be alone on our planet until scientists finally managed to penetrate the Congo and discovered it’s cousin the okapi. Since we are so used to the giraffes of the savannah the okapi seems like the oddball. But fossils show that the modern giraffe plan is actually the odd man out.